On a chilly December day in 1935, a low hum rolled across the California sky. It wasn’t just the sound of engines – it was the voice of a new era. On December 17, in the hangars of Douglas Aircraft Company, a plane was born, destined to become more than just a winged machine. The world was never the same after the Douglas DC-3 took its first flight. It was simple as a good friend, reliable as an old oak, and versatile as a Swiss army knife. Today, nearly a century later, its silhouette still flickers in the skies – from the snowy reaches of Alaska to the sweltering jungles. This is the story of how a plane became a legend that endures.

The Birth of a Dream

It all began with a challenge. In the 1930s, American aviation was searching for a way to bring the skies closer to everyday people. Planes were flying, but passenger travel was for the daring or the wealthy. American Airlines needed a liner that could cross the States with comfort and dependability. That’s when Donald Douglas and his team rolled up their sleeves. They looked at their DC-2 – a decent plane, but cramped and finicky – and decided it was time for a real leap forward.

The DC-3 was born from that resolve. They made it wider and longer than its predecessor, with a rounded fuselage that held 21 passengers by day or 14 sleeping berths by night in the Douglas Sleeper Transport (DST) version. Two Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines, each pumping out 1200 horsepower, hummed steadily and confidently. The wings, smooth and sturdy, kept it aloft, and the retractable landing gear – a rarity back then – tucked away neatly in flight. When the first DC-3 lifted off over Santa Monica, the pilots grinned: it was easy to handle, forgave mistakes, and landed where others would’ve given up.

The Sky for Everyone

The DC-3 debuted in 1936, and airlines fell head over heels. American Airlines put it on routes spanning the country, from New York to Los Angeles. Passengers, used to rattling noise and bone-shaking flights, suddenly found flying could be comfortable. Soft seats, a warm cabin, and even stewardesses serving meals – it was luxury unheard of before. In a single year, it carried more people than all U.S. airlines had in the decade prior. By 1939, the DC-3 handled 90% of America’s passenger traffic. They called it the “flying bus” – simple, affordable, and open to all.

But it was more than a liner. Its short takeoff – just 300 meters – and ability to land on dirt made it a favorite in places where pavement was a luxury. In South America, it soared over the Andes. In Africa, it hauled cargo into the savanna. In Australia, it linked scattered outback towns. In the three years before the war, Douglas built over 600 DC-3s, and that was just the start.

The Call of War: C-47 “Dakota”

When the world erupted in 1941, the DC-3 donned a military uniform. It became the C-47 Skytrain – the workhorse of the Allies. They beefed up the fuselage, added a cargo door on the left side, and gave the cockpit a spartan simplicity. Sometimes they swapped the engines for Wright R-1820 Cyclones, but the core stayed the same – reliability. In Britain, they nicknamed it “Dakota,” and the name stuck like a trusty old call sign.

The Birth of a Dream

It all began with a challenge. In the 1930s, American aviation was searching for a way to bring the skies closer to everyday people. Planes were flying, but passenger travel was for the daring or the wealthy. American Airlines needed a liner that could cross the States with comfort and dependability. That’s when Donald Douglas and his team rolled up their sleeves. They looked at their DC-2 – a decent plane, but cramped and finicky – and decided it was time for a real leap forward.

The DC-3 was born from that resolve. They made it wider and longer than its predecessor, with a rounded fuselage that held 21 passengers by day or 14 sleeping berths by night in the Douglas Sleeper Transport (DST) version. Two Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines, each pumping out 1200 horsepower, hummed steadily and confidently. The wings, smooth and sturdy, kept it aloft, and the retractable landing gear – a rarity back then – tucked away neatly in flight. When the first DC-3 lifted off over Santa Monica, the pilots grinned: it was easy to handle, forgave mistakes, and landed where others would’ve given up.

The Sky for Everyone

The DC-3 debuted in 1936, and airlines fell head over heels. American Airlines put it on routes spanning the country, from New York to Los Angeles. Passengers, used to rattling noise and bone-shaking flights, suddenly found flying could be comfortable. Soft seats, a warm cabin, and even stewardesses serving meals – it was luxury unheard of before. In a single year, it carried more people than all U.S. airlines had in the decade prior. By 1939, the DC-3 handled 90% of America’s passenger traffic. They called it the “flying bus” – simple, affordable, and open to all.

But it was more than a liner. Its short takeoff – just 300 meters – and ability to land on dirt made it a favorite in places where pavement was a luxury. In South America, it soared over the Andes. In Africa, it hauled cargo into the savanna. In Australia, it linked scattered outback towns. In the three years before the war, Douglas built over 600 DC-3s, and that was just the start.

The Call of War: C-47 “Dakota”

When the world erupted in 1941, the DC-3 donned a military uniform. It became the C-47 Skytrain – the workhorse of the Allies. They beefed up the fuselage, added a cargo door on the left side, and gave the cockpit a spartan simplicity. Sometimes they swapped the engines for Wright R-1820 Cyclones, but the core stayed the same – reliability. In Britain, they nicknamed it “Dakota,” and the name stuck like a trusty old call sign.

The C-47 was a hero of World War II. On June 6, 1944 – D-Day – hundreds of these planes dropped paratroopers over Normandy. They towed gliders packed with soldiers, carried medical supplies, and evacuated the wounded. In Burma, they supplied troops across the Himalayas on the “Hump,” one of history’s most perilous routes. General Dwight Eisenhower called the C-47 one of four key tools of victory, alongside the jeep, the truck, and the rifle. By war’s end, over 10,000 Dakotas had been built, each bearing the scars of battle.

Pilots loved its grit. It could fly on one engine, belly-land, and take punishment that would’ve torn others apart. One C-47 even limped home with a hole in its wing the size of a man – and still made it. After the war, thousands of Dakotas stayed in service, passing into civilian hands to keep on flying.

Peace and New Horizons

When the guns fell silent, the DC-3 didn’t retire. Its affordability and simplicity made it king of the postwar skies. In Europe, it helped rebuild airlines. In Asia, it hauled rice and cloth. In America, it became the go-to plane for small outfits. Everyone used it – from smugglers to missionaries. In 1948, during the Berlin Airlift, C-47s flew round the clock, delivering coal and food to a besieged city, proving they could save not just soldiers but entire communities.

It flew everywhere. In Antarctica, they fitted it with skis and sent it to polar stations. In jungles, it landed on strips hacked out of the forest. In mountains, it carried cargo where helicopters hadn’t yet ventured. By the 1950s, the DC-3 was the most produced plane in history – over 16,000 units, including military and licensed versions like the Soviet Li-2 or Japanese L2D.

The Soul of the Machine

What made the DC-3 special? Its design was brilliantly simple. A rugged all-metal fuselage, tough as a tank, stood up to years of service. Wings with their gentle curve gave lift even at low speeds. The engines – Twin Wasp or Cyclone – were unfussy, repairable in the field with minimal tools. The landing gear, though not always flawless, took the brunt of dirt and rocks.

But the real magic was its soul. Pilots swore the DC-3 talked to them. One veteran recalled, “You felt its vibration, heard its hum, and knew it wouldn’t let you down.” Another joked, “If you’re lost, just let go of the stick – it’ll find its way home.” It was a machine with personality, teaching generations of aviators to fly.

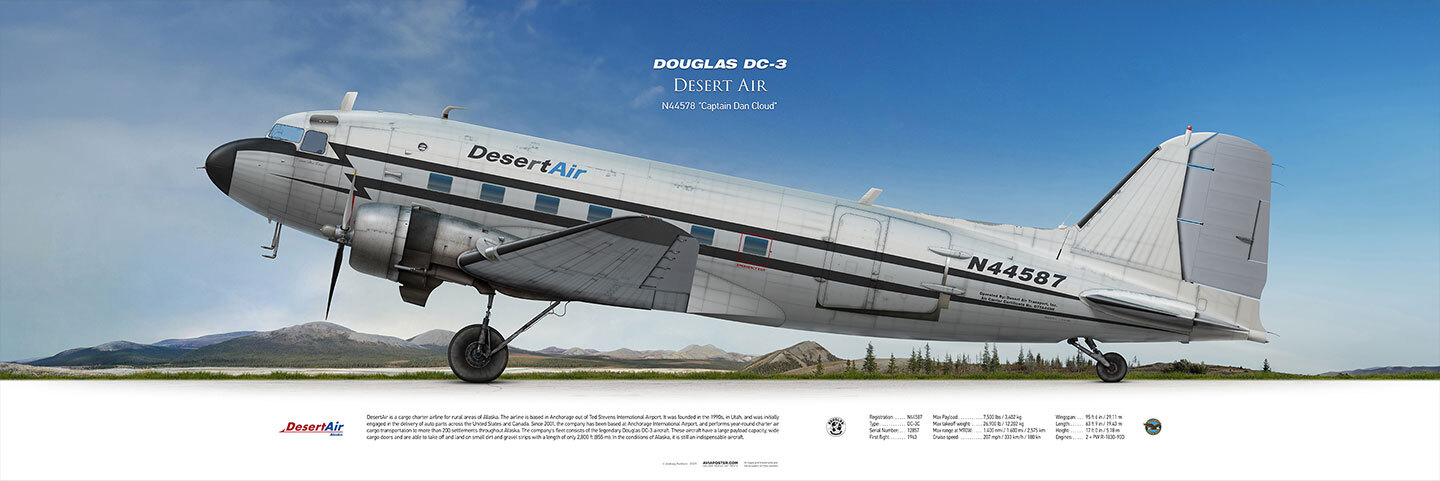

Today, the DC-3 isn’t just history – it’s alive. Somewhere in the Arctic, it hauls cargo to villages with no roads. In Colombia, it dives into jungles, carrying everything from medicine to mail. In Australia, they cherish it not in museums but in the air. They say about 400 are still flying – some count more, some less, but the truth holds: they don’t quit.

Our poster of a flying DC-3 isn’t just a picture. It’s a reminder that some things outlast time. That plane might be one humming over Alaska, joined by two of its modified kin. Each is a piece of 1935, still living, breathing, and soaring.

Why It’s Eternal

The DC-3 wasn’t the fastest – jets outran it by the 1950s. It wasn’t the biggest – a Boeing 747 dwarfs it. But it was the best at what it did. It was built for people, not records. It connected cities and nations, saved lives, and opened horizons. They made it to last forever, and it’s kept that promise.

Sometimes I wonder what Donald Douglas would say, seeing his “child” in the skies of 2025. He’d probably smile. Because the DC-3 isn’t just a plane. It’s a dream that took off one winter day and still hasn’t landed.

New Wings for an Old Friend

Other Modifications of the DC-3

The story of the Douglas DC-3 began in December 1935, when it first broke free from the earth, carrying aloft not just metal and engines, but dreams of aviation that could be accessible and reliable. This plane became a legend, its twin-engine silhouette familiar to anyone with even a passing interest in flight. But few know that the DC-3 didn’t freeze in time – it grew, sprouting new versions, modifications, and even wild experiments, including astonishing three-engine variants. Let’s take a journey through these lesser-known pages of its history and see how an old friend found new wings.

The First Steps: DST and Early Days

It all started with the Douglas Sleeper Transport, or simply DST. This was the first chapter in the DC-3’s evolution, sparked by a request from American Airlines. They wanted a plane that could cross the continent at night, offering passengers cozy sleeping quarters. In Douglas’s workshops, they took the DC-2 as a starting point, stretched the fuselage, made it wider and rounder, and fitted it with seven compartments, each with a pair of fold-down bunks. By day, it could carry up to 28 passengers; by night, it transformed into a flying hotel for 14. The first DST took off the same day as the baseline DC-3, December 17, 1935, setting the stage for every version to come.

But the DST was just the beginning. Soon came the civilian DC-3A, powered by beefier Pratt & Whitney R-1830 Twin Wasp engines that churned out up to 1200 horsepower. Then followed the DC-3B – a rare bird ordered by TWA with an even more luxurious cabin. These planes crisscrossed America, carrying passengers in a level of comfort that was the stuff of dreams back then. But the world kept turning, and the DC-3 was ready for new roles.

A Soviet Cousin: The Li-2

Meanwhile, across the ocean in the USSR, the DC-3 found a new life. In 1936, the Soviet Union bought a handful of planes from Douglas and soon decided to build their own. At first, they assembled them from American parts under the name PS-84, but by 1939, full-scale production kicked off. Thus was born the Li-2, named after designer Boris Lisunov, who tweaked the project to fit Soviet realities.

The Li-2 was different from the original. Instead of American engines, it got M-62IRs – a local take on the Wright Cyclone, slightly less powerful but familiar to Soviet mechanics. The fuselage stayed nearly the same, but the interior was reworked to meet national standards and needs. During the war, the Li-2 ferried soldiers, dropped supplies to partisans, and even moonlighted as a night bomber. After the war, it became Aeroflot’s workhorse, soaring across the vast Soviet expanse. Nearly 5000 were built by 1952, and some still rest in museums, silent witnesses to those days.

The Japanese Path: Showa L2D

On the other side of the world, in Japan, the DC-3 took on yet another form. Before the war, the Japanese bought a license from Douglas and began producing their own version, the Showa L2D. Built at Showa and Nakajima factories, around 487 planes rolled out between 1939 and 1945. Visually, the L2D was almost a twin of the original, but its engines varied – most often fitted with Mitsubishi Kinsei, a Japanese design that delivered a bit less power than the American motors.

The L2D served in Japan’s Air Force and Navy, hauling cargo and troops across the Pacific theater. After the war, surviving planes fell into Allied hands, and some even kept flying for civilian airlines in Southeast Asia. It was another testament to how the DC-3 adapted to foreign skies and foreign needs.

Three-Engine Dreams: DC-3S and Experiments

But what if two engines weren’t enough? In the late 1940s, Douglas pondered how to breathe new life into the DC-3. Enter the DC-3S, also known as the Super DC-3. Engineers took two old planes, stretched the fuselage, added space for 38 passengers instead of 30, and shifted the wing back for better stability. The real goal, though, was to make it faster and stronger. They swapped in Wright R-1820 Cyclone 9 engines with more thrust and fitted four-blade props. When the first DC-3S took off in 1951, it delivered: speed climbed to 400 km/h, and range stretched to 3000 km.

Sadly, the Super DC-3 never caught on widely. Postwar markets were flooded with cheap C-47s, and airlines weren’t eager to buy a new variant. Only a few were built, most going to the military – like the U.S. Navy, where they flew as R4D-8s. Still, the idea showed the DC-3 could grow and evolve.

Now, here’s a surprise: there were three-engine DC-3s! In the 1940s, U.S. engineers toyed with adding a third motor. One project stuck an extra engine in the nose, right above the cockpit. It looked bizarre, like something from an old sci-fi flick, but it worked, giving more power for heavy loads and high-altitude flights. Another experiment mounted the third engine in the tail, echoing some trimotors of the era. These stayed prototypes, never reaching production – war and the rise of jets put an end to the bold schemes. But they proved engineers saw endless potential in the DC-3.

Unusual Kin: From Floats to “Spooky”

The DC-3 wasn’t bound to land. In the 1940s, a floatplane version emerged, able to set down on water. These were used in Canada and Alaska, delivering cargo to places without airstrips. Floats were bolted under the fuselage, and the structure was reinforced to handle waves. A rare sight, but indispensable in its niche.

In Vietnam, the DC-3 turned warrior. The AC-47 Spooky, an armed C-47 variant, bristled with three machine guns on its side, becoming a nighttime terror for enemies. Nicknamed “Puff the Magic Dragon” for its firepower and low engine rumble, Spooky circled targets, raining lead below. It became a war legend, showing the DC-3 could be anything – from a passenger liner to a gunship.

A Legacy That Lingers

Every DC-3 modification tells a story of a brilliant foundation that thrived for decades, adapting to new times. From the cozy DST to the fearsome Spooky, from the Soviet Li-2 to three-engine dreams, this plane proved it was more than machinery. It was a symbol of an age when aviation was an adventure, and engineers dared to imagine.

Today, vintage DC-3s and their descendants still fly – some in museums, others in remote corners of the world. As long as their familiar hum echoes in the sky, one thing’s certain: this old-timer hasn’t said its final word. Who knows? Maybe somewhere in a hangar, a new variant is taking shape, waiting to spread its wings tomorrow.